Scribble trajectories: building an online handwriting transformer

Introduction

At the end of last year, I spent months at Recurse Center diving deep into theory and state-of-the-art research (EBMs, VAEs, transformers, diffusion models, RL, etc) while revisiting the math-heavy fundamentals of machine learning. Now, I’m back to building.

I found online handwriting generation — predicting pen strokes in real time — to be a great exploration for robotic trajectory modeling. A robot follows continuous motor commands (e.g. Δx and Δy) plus discrete events (e.g. gripper opens), just like handwriting sequences combine fine-grained movement (in a 2D trajectory) with pen lifts. And namely, I already had access to a great handwriting dataset and could train within a reasonable time (though I did upgrade to Colab Pro+).

My primary goal was to gain hands-on experience building a multimodal transformer end to end: from tokenizing data to training and visualizing results. My broader goal is to scale these ideas into large foundation models that can produce continuous movements, like robotic actions.

I’ll go over:

- How I represent Δx, Δy, pen lift events

- Why a discrete transformer worked best

- Shifting to multitask, multimodal modeling

- Key debugging tricks (attention visualization, mini-datasets)

- Ties to robotic transformers like RT-Trajectory

- Future directions toward foundation models with text and continuous movements

Where robotics fits in

Connecting to SOTA robotics transformers

-

RT-2

- What it is: RT-2 from Google DeepMind treats robot actions as text tokens. That way, it can take any vision-language model and fine-tune it into a vision-language-action model. During inference, the text tokens are decoded into continuous robot actions for closed-loop control.

- Why it relates: This approach views motor commands as another language, just like how strokes could become discrete tokens in a handwriting language.

-

RT-Trajectory

- What it is: RT-Trajectory, also from DeepMind, uses trajectories as a way to specify robot tasks. It captures similarities between motions across different tasks, improving generalization beyond language-only or image-only approaches.

- Why it relates: Handwriting is already composed of 2D stroke movements, similar to these 2D trajectory sketches. By learning from 2D or 2.5D trajectory representations, RT-Trajectory shows how specifying a drawn path can yield robust policy generalization since it’s easier to interpolate or adapt new motions.

-

Pi-0

- What it is: Pi-0, from Physical Intelligence, integrates vision, language, and proprioception into a single embedding space. It uses action chunking and flow matching to model complex continuous actions at high frequencies up to 50 Hz.

- Why it relates: Handwriting generation deals with trajectories at lower frequencies, but the principle is the same: refine trajectory generation in a globally coherent way.

-

HAMSTER

-

What it is: HAMSTER is a hierarchical vision-language-action approach from NVIDIA/UW/USC that came out after the first draft of this blog post. It trains a large VLM to produce a coarse 2D path, then hands that path off to a smaller, 3D-aware policy for precise manipulation. Super relevant, so I’ll dig into this one more!

-

How trajectories help:

-

Learning in robotics often struggles because of:

- Expensive on-robot data: Collecting huge labeled image-action datasets is time-consuming and costly.

- Overly specialized policies: A monolithic vision-action model tends not to generalize well to new tasks or embodiments.

- Inference frequency constraints: Large VLMs can’t always run at the frequency (e.g. 50Hz) needed for fine, real-time control.

-

HAMSTER solves this by predicting a 2D path in the camera image, keeping the VLM embodiment agnostic. It doesn’t need any details about the robot shape or degrees of freedom: just marks where to move in 2D space. A smaller, specialized policy then converts that path into precise 3D actions for whatever robot is actually used.

-

-

Leveraging off-domain data:

-

Because HAMSTER only needs 2D trajectories rather than explicit robot actions, it can fine-tune on cheaper data sources (e.g. action-free videos or physics simulations) using:

- Point tracking: track a person’s hand or object in a video

- Hand-sketching: a human sketches the path directly on an image

- Proprioceptive projection: known joint positions are projected onto a 2D camera view

-

-

Why it relates: HAMSTER focuses on robotic manipulation, but 2D trajectories apply equally to handwriting. We can find endless images of text online but lack stroke-by-stroke datasets. If we just approximate or extract 2D strokes from those images, a large VLM could propose coarse strokes that a smaller policy refines into Δx, Δy commands.

-

These approaches cover vision-language data, 2D trajectories, and a separation of coarse and fine control, and highlight how trajectory-based representation can better use foundation models for precise motion policies. Online handwriting is essentially a 2D trajectory plus a “lift pen” signal, so I thought about modeling my data in the way that a robot model might tokenize joint and gripper signals.

Model development

Stage 1: data representation and early models

1) Δx, Δy, pen lift Format

I started with a handwriting stroke dataset where each sequence consists of variable-length timesteps, each represented by three values:

- Δx: movement in x from the previous point

- Δy: movement in y

- pen lift ∈ {0, 1}: is the pen on paper or lifted?

2) GMM approach

Alex Graves’ classic handwriting approach uses an RNN and mixture density network (MDN) to model continuous stroke distributions.

Click for details on how I started with that approach

- MDN background

- Gaussian Mixture Model: A probabilistic approach assuming data arises from multiple Gaussian distributions, each with its own mean, variance, and mixture weight.

- Mixture Density Network: A neural network that outputs the parameters of a GMM at each timestep, giving a continuous distribution over Δx and Δy.

-

Why I started with this approach

- I wanted to be able to capture continuous variability in handwriting, like subtle style differences or loopy letters.

- MDNs can represent multi-modal distributions, like multiple ways to draw the letter “a”.

-

Pitfalls

- Mode collapse: The MDN almost always converged to a single mixture component, producing monotonic diagonal movements—either up and to the right or down and to the left—regardless of text conditioning. This happened because it consistently picked the same Gaussian with a small variance range.

- Too many hyperparameters: Balancing mixture weights (π), correlation (ρ), temperature, and entropy constraints required a lot of tuning. Since I was paying for my own training compute, I did not have the capacity to run so many experiments.

- Unstable training: Subtle issues like exploding gradients or near-zero σ caused frequent NaNs or seemingly random outputs.

It took time to dig into the model outputs and realize that mode collapse was causing this behavior. The model was always choosing the same Gaussian distribution, leading to repetitive, unnatural stroke patterns. This realization led me to shift toward discrete tokenization, which eliminated that unnatural diagonal stroke bias.

My takeaway was that discrete transformers would be far simpler and more stable.

- Tokenized approach fits transformers: Transformers excel at tokenized data, and binning Δx and Δy allowed me to use standard classification and cross-entropy.

- Tokenization works with the data: Handwriting deltas span a small range, so discretizing them doesn’t sacrifice much resolution or smoothness.

- No continuous sampling quirks: Inference just relies on picking the next token from a softmax distribution.

- Easier debugging: Digging into stroke tokens or mispredicted pen-lift is way easier than debugging multi-dimensional Gaussians.

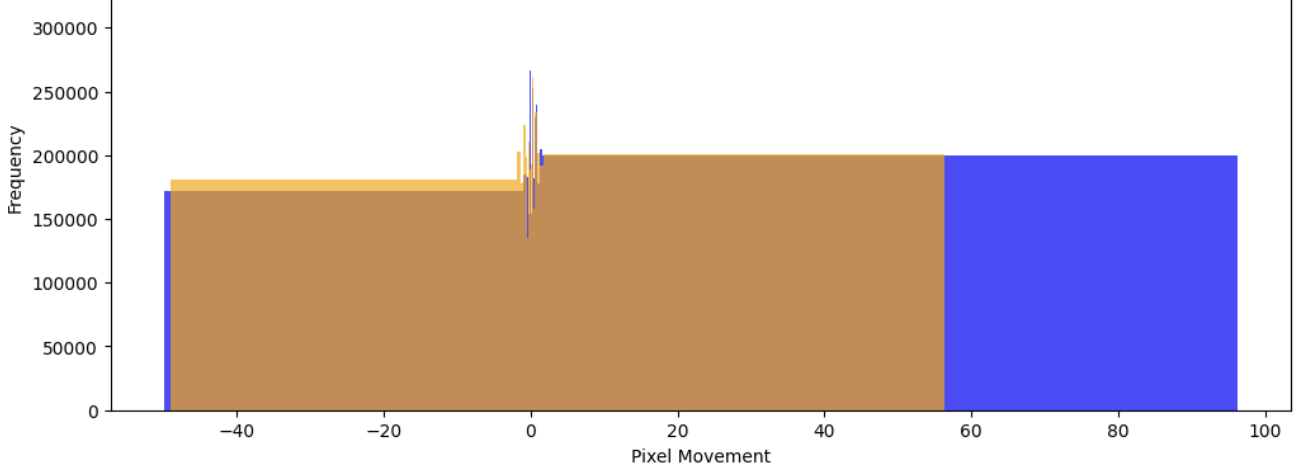

3) Tokenizing handwriting strokes

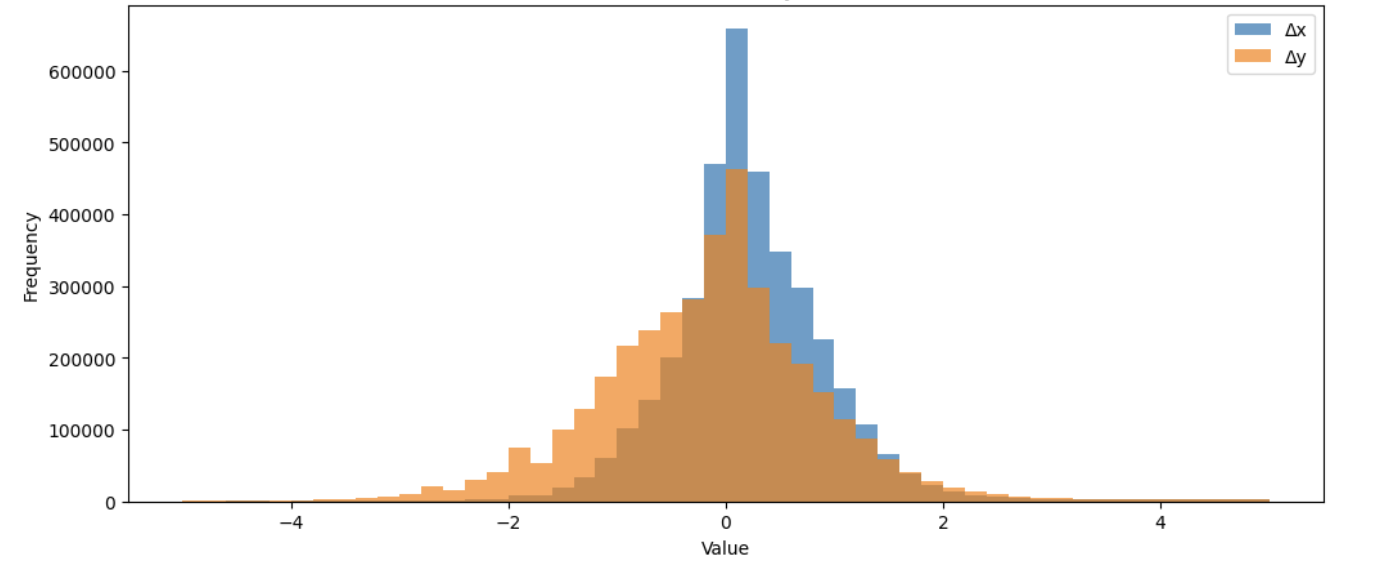

First, I generated discrete bins of Δx and Δy to tokenize the continuous values. From the raw values below, you can see how most movements in the dataset are small and clustered around zero, while larger movements are significantly less frequent.

I implemented adaptive binning, processing Δx and Δy into 24 bins each, making it easy for the transformer to autoregressively predict the next best move.

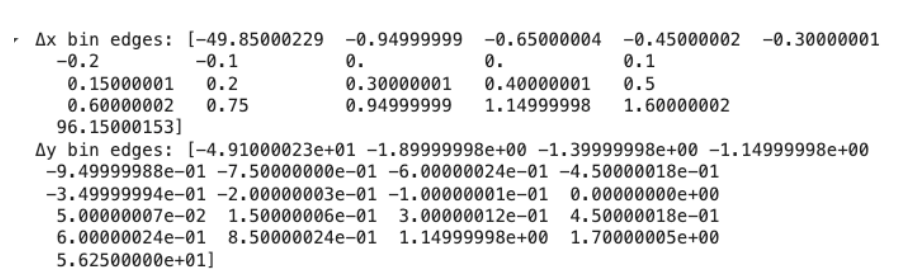

Click for adaptive binning details

-

Fine resolution near zero

Most strokes are small movements around Δx, Δy. By using uniform bins around zero, where most handwriting variations occur, the model can distinguish subtle pen movements. -

Log-spaced tails

Large movements are less frequent but can be significant (fast scribbles, big jumps). Logarithmic spacing ensures that minimal bins are assigned for these rare events while still capturing them. -

Adaptive refinement

Merge any bins with low data counts and adding extra bins where data was densest, maintaining a well-spaced distribution.Computed bin edges after adaptive binning:

Now, Δx and Δy are evenly distributed in their token classes. Small pen adjustments and larger strokes are properly represented, whereas uniform binning would have wasted resolution on rare big moves.

Great! Now the model can just classify the next token with standard cross-entropy loss, rather than needing to regress to floating-point values.

4) Implementing a tokenizer

At first, I used tiktoken, the tokenizer for GPT-4 with a 100K subword vocabulary. When my model wouldn’t converge, the first “duh” moment was that it was obviously overkill for my simple dataset and use case. I wrote a custom ASCII tokenizer of just 96 characters.

Click to see that implementation

class CharTokenizer:

def __init__(self):

self.pad_token = "[PAD]"

self.unk_token = "[UNK]"

ascii_punct = string.punctuation

chars = (

list(string.ascii_lowercase)

+ list(string.ascii_uppercase)

+ list(string.digits)

+ list(ascii_punct)

+ [" "]

)

self.itos = [self.pad_token, self.unk_token] + chars

self.stoi = {ch: i for i, ch in enumerate(self.itos)}

self.vocab_size = len(self.itos)

def _preprocess_text(self, text: str) -> str:

text = (

text.replace("’", "'")

.replace("‘", "'")

.replace("“", '"')

.replace("”", '"')

.replace("—", "-")

.replace("–", "-")

)

text = re.sub(r"[^\x20-\x7E]", "", text)

return text

def encode(self, text: str, max_length: int = 50) -> list:

text = self._preprocess_text(text)

tokens = [

self.stoi[ch] if ch in self.stoi else self.stoi[self.unk_token]

for ch in text

]

# Truncate if too long

tokens = tokens[:max_length]

# Pad if too short

tokens += [self.stoi[self.pad_token]] * (max_length - len(tokens))

return tokens

def decode(self, token_ids: list) -> str:

return "".join(

self.itos[idx] if 0 <= idx < len(self.itos) else self.unk_token

for idx in token_ids

)

5) Generating unconditional handwriting with a transformer

I first tested a transformer that generated new strokes based on previous strokes:

- Self-attention on stroke tokens The transformer processes each token (Δx, Δy, pen lift), learning how strokes typically flow over time.

- Scribble-like outputs With no text to guide it, the model produces free-form strokes. These can look like letters or loops, confirming it can generate coherent movement patterns before adding text conditioning.

- Advantages over RNN Transformers better capture long-range dependencies through self-attention, and discrete token classification avoids the complexities of continuous sampling or GMM instability.

Stage 2: shifting to conditional generation (text-to-handwriting)

Alignment and sequence length

Now it was time to make the model more useful and multimodal. I wanted to input text (e.g. “Hello world”) and produce realistic handwriting for it, so I:

- Used an encoder for text tokens, incorporating positional encodings to preserve character order.

- Used a decoder for stroke tokens, applying cross-attention so that each stroke prediction could reference the text.

Conditional generation

- Encoder-decoder architecture: The decoder queries the text encoder at each step, reinforcing the relationship between characters and strokes.

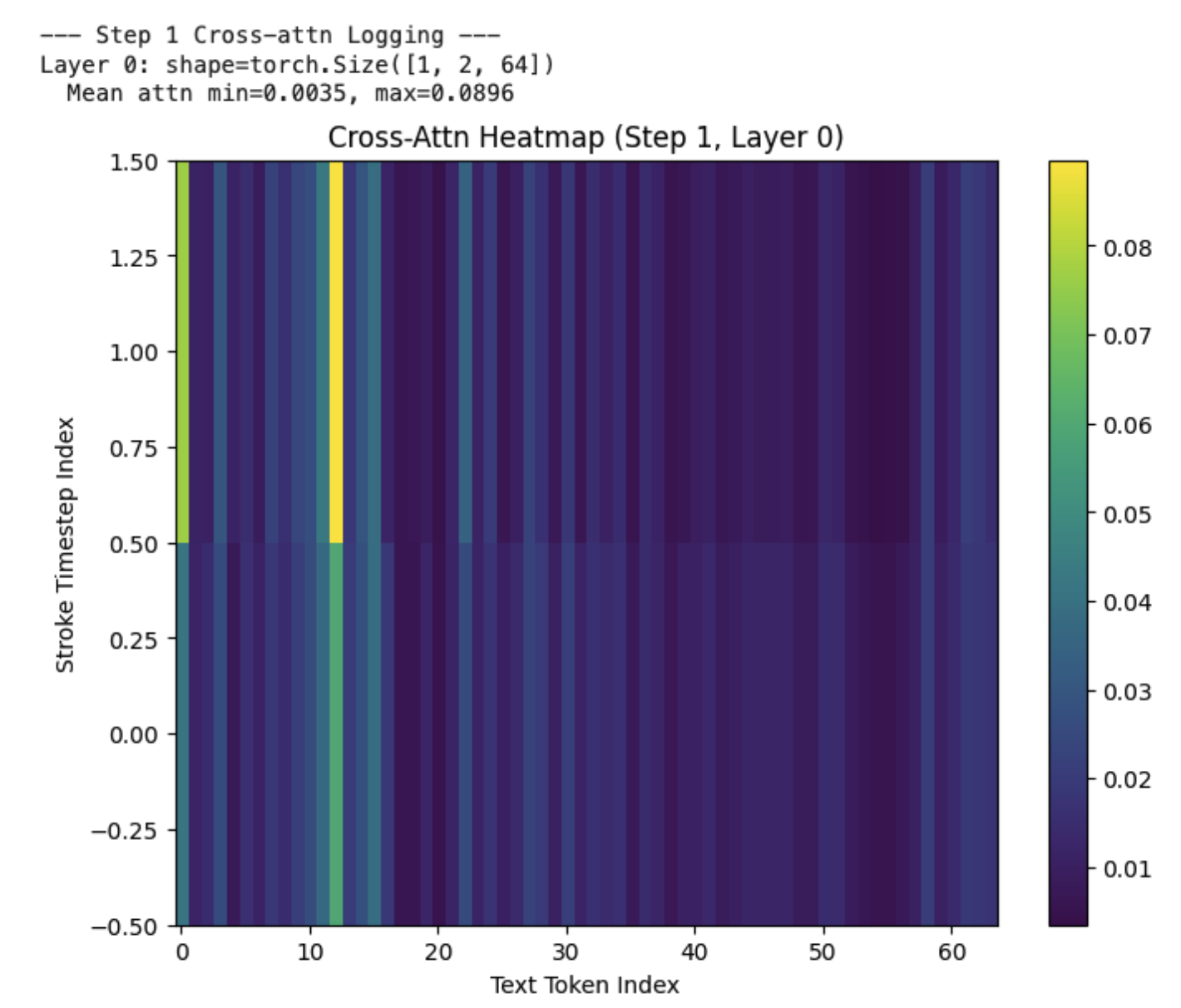

- Pad masking: Since text sequences vary in length,

[PAD]tokens were masked so the model wouldn’t attend to non-character tokens. - Cross-attention validation: I monitored attention matrices to ensure stroke tokens referenced text embeddings when text was present, while still autoregressing correctly on strokes when text was absent. If attention was uniformly distributed across text tokens, it indicated the model was ignoring the text, requiring adjustments to positional encodings or cross-attention layers.

This text-conditioned generation allowed the model to map language directly onto structured, sequential handwriting motion.

Click to see that implementation

class TransformerStrokeModel(nn.Module):

/* ... */

def _generate_causal_mask(self, seq_len, device):

mask = torch.triu(torch.ones(seq_len, seq_len, device=device), diagonal=1)

return mask.masked_fill(mask == 1, float('-inf'))

def forward(self, stroke_batch, text_features=None, text_pad_mask=None, return_attn=False):

b, t, _ = stroke_batch.shape

x_x = self.embedding_x(stroke_batch[:, :, 1])

x_y = self.embedding_y(stroke_batch[:, :, 2])

combined = torch.cat([x_x, x_y], dim=-1)

combined = self.fc_embed(combined)

combined = self.position_encoding_strokes(combined)

/* ... */

decoded, cross_attn_list = self.decoder(

combined, text_features,

tgt_mask=causal_mask,

return_attn_weights=True,

memory_key_padding_mask=text_pad_mask,

)

logits_x = self.fc_out_x(decoded)

logits_y = self.fc_out_y(decoded)

pen_logits = self.fc_pen_lift(decoded).squeeze(-1)

/* ... */

Stage 3: debugging strategy

Overfitting on one example, then five, then more

- When my model couldn’t memorize one text-stroke pair, I knew I had a model architecture or data processing bug.

- Then I’d test 5 pairs to see if it could overfit. Then 10, then 100.

- Only after that would I expand to the full dataset.

Oops moments

- Swapped Δx and pen lift: In one run, Δy looked great but the rest was off, and I discovered I had columns reversed in the batch. Simple fix.

- No positional encodings for text: Without them, the cross-attention was relatively random. Once I added

PositionalEncoding, the attention matrix aligned strokes with the correct characters in order.

Stage 4: architecture tweaks

Simplify

An underlying theme was paring down complexity. For instance, I started experiments with 8–12 heads and 6–8 layers, but quickly learned that was overkill that slowed down training. 2–4 heads and 1–3 layers converged way faster and were easier to debug.

Visualizing attention weights in PyTorch

While debugging, a huge interpretability boost was subclassing nn.TransformerDecoderLayer to return cross-attention weights. Plotting them as heatmaps (stroke_tokens × text_tokens) let me check alignment and quickly debug a bunch of situations (e.g. text completely ignored, positional encodings ignored, everything fixated on the first letter).

Click to see that implementation

class CustomDecoderLayer(nn.TransformerDecoderLayer):

def __init__(self, d_model, nhead, dim_feedforward=1024):

super().__init__(d_model, nhead, dim_feedforward=dim_feedforward, dropout=DROPOUT, batch_first=True)

def forward(

self,

tgt,

memory,

tgt_mask=None,

memory_mask=None,

tgt_key_padding_mask=None,

memory_key_padding_mask=None,

return_attn_weights=False

):

x, self_attn_weights = self.self_attn(

tgt, tgt, tgt,

attn_mask=tgt_mask,

key_padding_mask=tgt_key_padding_mask,

need_weights=return_attn_weights

)

tgt = tgt + self.dropout1(x)

tgt = self.norm1(tgt)

x, cross_attn_weights = self.multihead_attn(

tgt, memory, memory,

attn_mask=memory_mask,

key_padding_mask=memory_key_padding_mask,

need_weights=return_attn_weights

)

tgt = tgt + self.dropout2(x)

tgt = self.norm2(tgt)

x = self.linear2(self.dropout(self.activation(self.linear1(tgt))))

tgt = tgt + self.dropout3(x)

tgt = self.norm3(tgt)

if return_attn_weights:

return tgt, self_attn_weights, cross_attn_weights

else:

return tgt, None, None

Stage 5: refining conditional generation

With the basics working, I could now focus on more interesting tweaks, like:

- pen lift weighting. The pen was only lifted 5% of the time in the dataset, so I used focal loss.

- Temperature sampling to prevent repetitive loops at inference time.

- Occasional no-text to handle both the conditional and unconditional tasks.

Stage 6: final results and observations

Plenty of good:

- Human-like cursive or printed letters, with real pen lifts.

Some not-so-good:

- Over-smoothing: some letters lost distinct edges.

- Spacing: sometimes too tight or too wide.

I spent a lot of time visualizing:

- Plotting each epoch’s output.

- Seeding with real strokes for X timesteps, letting the model complete the rest.

Example outputs

Click for early MDN generation

Identifying the issue

- The generated strokes consistently move up and to the right, revealing that the model always selects the same Gaussian component instead of adapting to the handwriting context.

- Even though the transformer theoretically improved long-range dependencies, the unstable MDN head remained a bottleneck, producing repetitive trajectories.

- A shift to discrete tokenization was necessary to give the transformer better control over individual stroke outputs, avoiding the need for unstable mixture sampling.

After trying a lot of hyperparameter tuning and model tweaks, I switched to discrete tokens, which eliminated this issue.

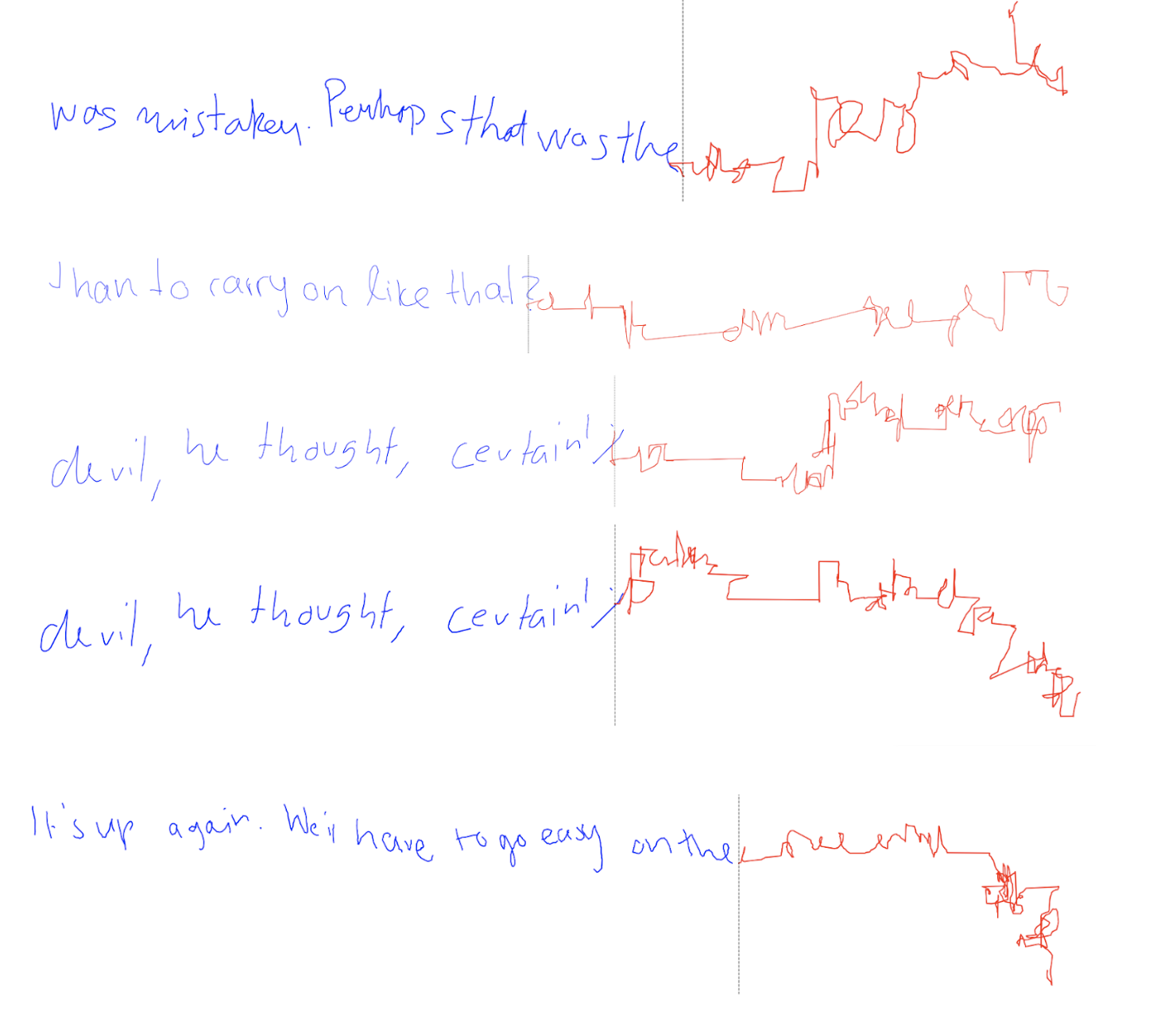

Click for early discrete transformer generation

In this example, I seeded the model with some strokes from the dataset (in blue) and let it generate the remaining handwriting (in red) based on both strokes and text. Early on, the model produced fragmented and erratic strokes.

Identifying the issue

- The generated strokes frequently lost coherence, failing to maintain the structure of letters beyond a few timesteps.

- This early output helped diagnose issues with:

- cross-attention alignment: ensuring the model properly conditions on text instead of generating arbitrary strokes.

- stroke continuity: adjusting positional encodings and training dynamics to prevent erratic jumps.

- autoregressive stability: the model struggled to smoothly transition from real strokes to generated ones.

As training progressed, I refined the text-stroke relationship, improving overall performance.

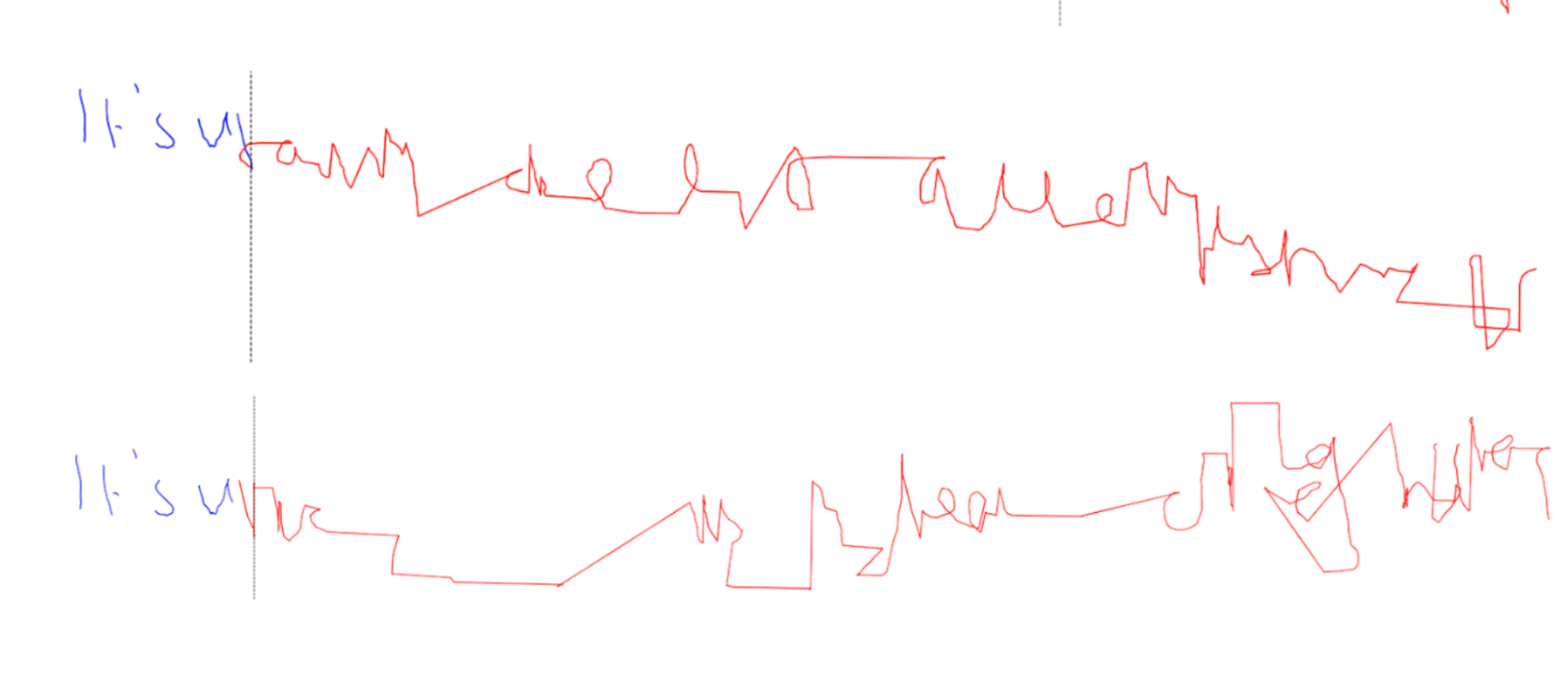

Click for pen lift failure due to imbalanced data

After some refinements on the above, the model still failed to lift the pen correctly.

Identifying the issue

- The model struggled with pen lifts, treating them as rare occurrences and failing to separate letters properly.

- This happened because lift events were underrepresented in the dataset, making the model biased toward keeping the pen down.

Fixing it with focal loss

- I introduced focal loss, which increases the weight of rare events during training.

Click for positional text encoding fix

After the above, I finally got the model producing reasonable letter-like scribbles, but they were still jumbled and nonsensical, failing to follow the intended character sequence.

Identifying the issue

- The model appeared to understand what letters should look like, but had no sense of where to place them in relation to the input text.

- This is because positional encodings were missing from the text encoder, meaning the model saw all text tokens as unordered symbols rather than a structured sequence.

Fixing it with positional encodings

- With this fix, the model could associate text positions with stroke positions, improving letter placement and structure.

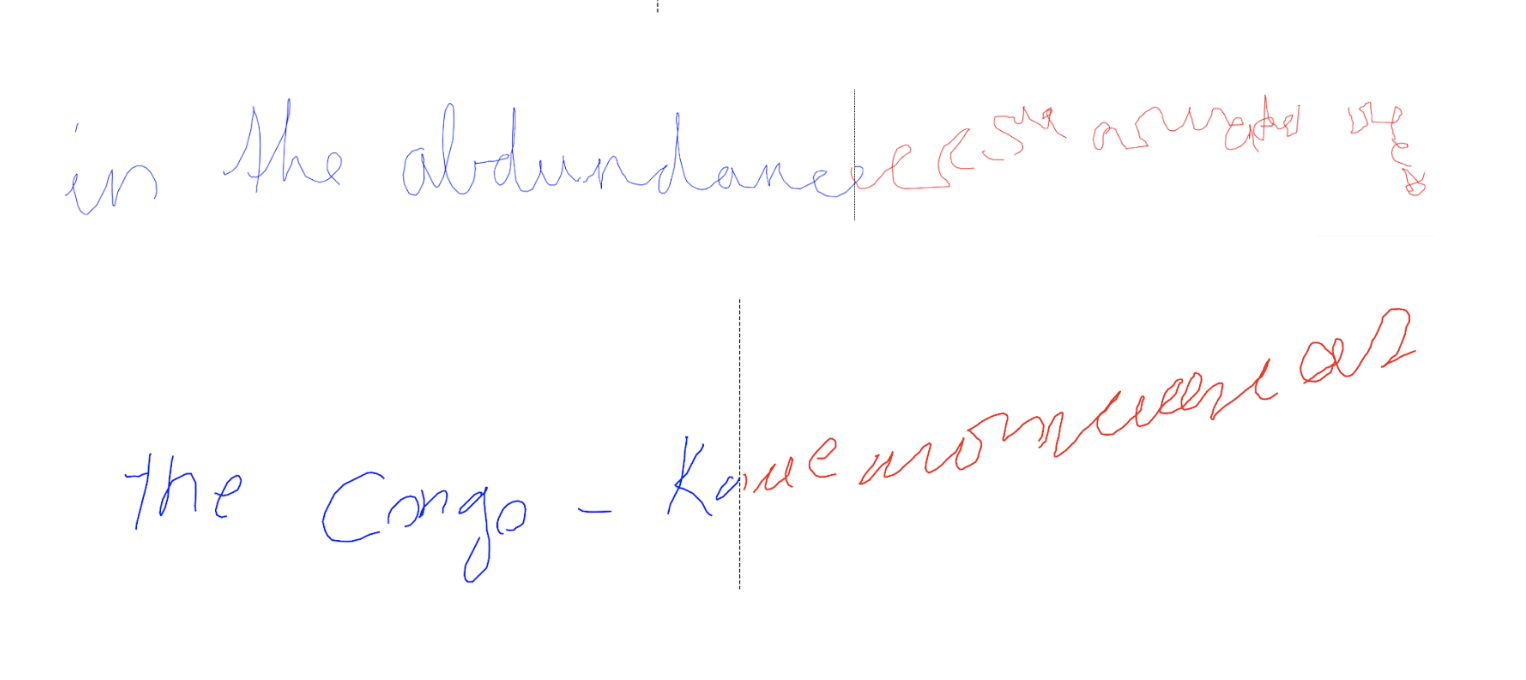

Improved handwriting generation

And finally… successful text-to-handwriting generation!

What works here

- The generated handwriting follows the structure of the input text, properly aligning strokes with corresponding letters.

- Pen lifts and spacing works.

- The handwriting flows naturally vs. wild nonsensical movements from earlier models.

Key improvements that led to this result

This level of convergence required many iterations of model architecture refinement, hyperparameter tuning, and targeted loss reductions.

- Model architecture improvements: I reduced the number of Transformer layers and heads to 2–4 heads, 1–3 layers, balancing expressiveness and convergence speed. Larger models took longer to learn without necessarily improving output quality.

- Hyperparameter tuning: Learning rate schedules, warm-up steps, and batch size adjustments helped stabilize training and prevent overfitting, particularly by adjusting loss scaling on pen lift events.

- Loss function adjustments: Introducing focal loss helped pen lift balancing, while ensuring positional encodings were properly applied to both stroke and text tokens helped cross-attention learn better alignments.

- Improved cross-attention layers: Careful inspection of attention weights helped uncover bugs.

Stage 7: future directions and extensions

-

Handwriting to text

The inverse model is basically handwriting recognition. This closes the loop and could enable a single multimodal, multitask model that does handwriting generation and recognition. -

Style transfer

Condition on user-specific samples to replicate personal handwriting styles or emulate various fonts. With a small style embedding or reference strokes, the model can generate text in that style. -

Diffusion, VAEs, and EBMs

-

Diffusion models:

Instead of discrete or GMM-based sampling, a diffusion approach could produce smoother strokes by iteratively refining a noisy sequence. Latent diffusion models include a VAE-like encoder-decoder pipeline that compresses the data before applying the denoising process.-

Planning with Diffusion for Flexible Behavior Synthesis proposes a non-autoregressive method that predicts all timesteps concurrently, blurring the lines between sampling from a trajectory model and planning with it. Each denoising step focuses on local consistency (nearby timesteps in the past and future), but composing many of these steps creats global coherence. Applied to handwriting or robot motion, this approach can help ensure the entire stroke or trajectory is consistent, rather than being generated purely from past context in a causal manner.

-

Pi-0 replaces standard cross-entropy with a flow matching loss in a decoder-only transformer. They maintain separate weights for the diffusion tokens, effectively embedding diffusion within a vision-language-action pipeline to handle high-frequency action control. A handwriting model could do the same.

-

-

Variational autoencoders:

A VAE would encode Δx, Δy sequences into a latent space and then decodes them back into strokes, allowing style interpolation or manipulation in the latent space. -

Energy-based models:

EBMs define an energy function over data configurations. I spent a number of months studying EBM math and typical architectures, which helped when considering more flexible training objectives or capturing complex multimodal distributions. Going further in this direction could produce more robust handwriting outputs while reducing mode collapse.

-

-

Interactive demo

A web-based interface where users type text and see real-time text generation. Also great for collecting more data. -

Robotics

Expand from 2D pen strokes to 3D or 6D manipulator movements. The model’s text conditioning can guide a robot to write letters on a whiteboard or execute more complex tasks, similar to methods like RT-2 or Pi-0 that fuse language with action tokens in a transformer.

Conclusion: big-picture takeaways

-

Trajectory modeling

I used online handwriting as a small-scale example, but the same sequence-based ideas apply to bigger robotic tasks. Ongoing research increasingly relies on trajectory modeling for everything from gripper motions to mobile navigation. -

Foundation models and unified approaches

Even a few years ago, each robot component (vision, planning, action) was handled by a bespoke model. Now, vision-language-action pipelines show that tokenizing actions or strokes can use large, generalized models to handle more data and more tasks. -

Simple and incremental debugging

Overfitting tiny subsets (1–5 examples) quickly exposes data or model issues. Plotting attention matrices or partial outputs helped me a ton, and this incremental debugging approach has always been invaluable for me as an applied researcher within robotics and deep learning. -

Paths forward

Tokenizing continuous actions, conditioning on multiple modalities, and leveraging big models offer a route to robotic manipulation that unifies language, vision, and motion. Handwriting is small-scale, but the underlying principles transfer directly to complex systems.